Women in Rebellion: How Paramilitary Women Experienced the Troubles of Northern Ireland

Nicole Marion (COL’22) graduated from Georgetown University with a double major in both History and Government. She was a 2021-2022 Global Irish Studies Fellow.

Jackie was only 17 when she decided to join the Ulster Defense Association (UDA). By the time she was 20, she was an active combatant in the conflict in Northern Ireland known widely today as “the Troubles.” Although paramilitaries were some of the main actors in the conflict, Jackie was an anomaly: women, especially Loyalist women, we’re not often combatants, nor were they encouraged to be. However, Jackie, who had seen friends and family members fall victim to the attacks of Republican paramilitaries, was motivated by her passion to defend her community.

On the other side of the conflict was Sinéad Moore, a young teenager who had spent her entire young life watching her Catholic family and community being treated as second-class citizens. After witnessing Internment of prisoners without trial and the Bloody Sunday attack by British forces on a civil rights march, Sinéad joined the Irish Republican Army (IRA) determined to stop the injustice that she saw occurring. Jackie and Sinéad were two young women from two contrasting backgrounds who joined opposing sides of a conflict; yet the reasons they joined – stemming from a sentiment of injustice and a desire to defend their community – are almost identical. While Jackie and Sinéad were not the only women inspired to break tradition and join the fight, these women fighters are often overlooked and little is known about them.1

Republican and Loyalist paramilitary women during the Troubles exemplify a unique and necessary voice in the Troubles and in conflict scholarship. However, scholarship on Irish paramilitaries during the Troubles has largely focused on male activities. In more recent studies by scholars like Dieter Reinisch, Miranda Alison, and Sandra McEvoy, only one aspect of the women’s experience (for example, their initial motivation for joining) is analyzed. These women’s stories are by no means easy to uncover – oftentimes they are protected by male gatekeepers and referred to by pseudonyms. However, their voice is as vital to understanding paramilitary action during the Troubles as any. In my Senior Thesis, I aimed to compile and analyze the motivations, experiences, and identity of both Republican and Loyalist paramilitary women. In doing so, I hoped to gain a more complete understanding of the Troubles and of woman’s roles as combatants in national conflict.

One of the most interesting differences in the experiences of these two groups of women lies in how women were viewed within each community and paramilitary organization. Women in Republican groups claim to have experienced little sexism (though it was by no means non-existent) and felt that they belonged within predominantly male organizations like the IRA. One woman from a study done by Miranda Alison, Teresa, remembered how women who wanted to join the IRA were initially dismissed, but once they became official members were treated in exactly the same way as the men, both in terms of acceptance and the ways they were involved in the group’s missions. Moreover, Republican paramilitary women felt a strong connection with each other.

One of the most traumatizing experiences for many Republican women was the time they spent in Armagh prison after they were tried and found guilty for their involvement in paramilitaries: they were often strip-searched and assaulted, had their newborn babies taken from their arms, and were subject to grotesque living conditions. During this time, their struggles were largely unrecognized by the public, as male hunger strikers and protesters were the center of media attention. However, women engaging in similar protests to regain special category status in prisons faced a uniquely female dilemma. Their participation in the No Wash protest led to the smearing of both fecal matter and menstrual blood on the walls of the cells, as women were denied necessary sanitary products. Thus, for many women the purpose of this protest quickly expanded into the issue of women’s rights and how women were treated in the prison system. Although the experience was traumatic, Republican women found solidarity with each other, so much so that many felt guilty when they were released and their fellow prisoners stayed behind.

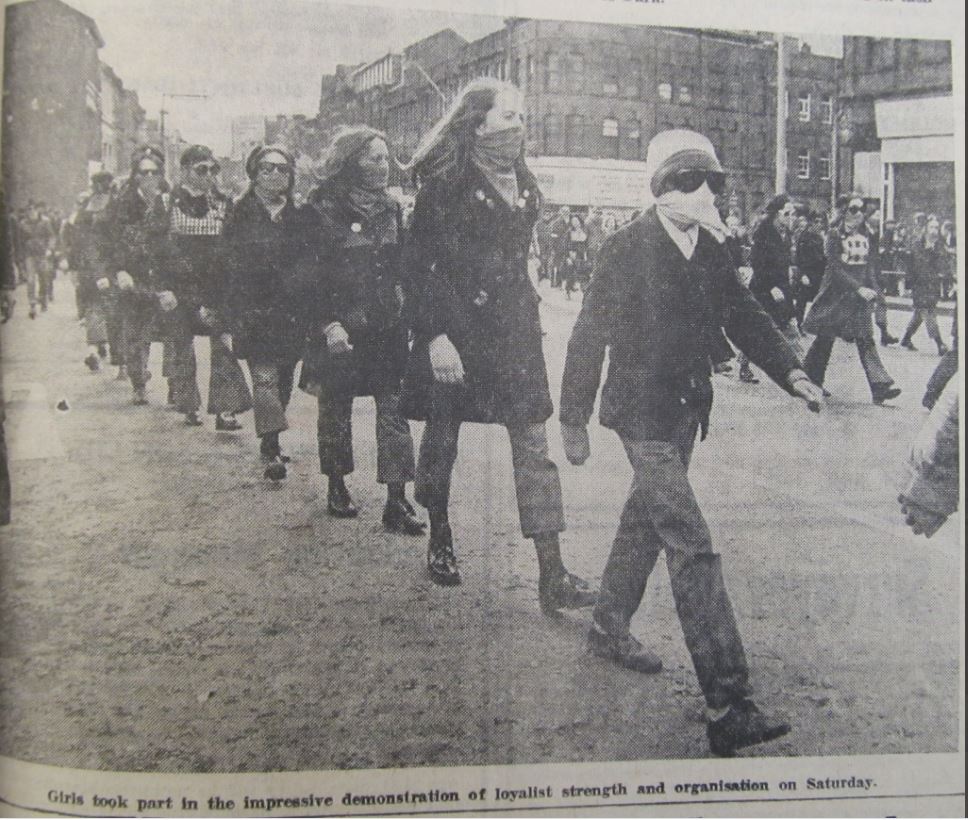

At the same time, Loyalist paramilitary women struggled simply to be accepted and recognized – a problem that exists in the movement to this day. They remember instances in which their male peers told them they should be home with children or in the kitchen, or asked for bigger guns than them. Across the few studies focused on Loyalist women by organizations such as the Training for Women Network and scholars such as Sandra McEvoy, Loyalist paramilitary women claimed that they were never involved in the same way that the men were, and believed they were underappreciated for their contribution to the cause. Many of these women experienced blatant sexism during their time in Loyalist paramilitaries. For example, Jackie remembered how even being affiliated with a Loyalist paramilitary as a woman implied that you were in a sexual relationship with the members of the group, and was looked down upon by the larger community. Furthermore, these Loyalist women – fewer in numbers than their Republican counterparts – never experienced the camaraderie in prison that Republican paramilitary women did. Often they were the only Loyalist prisoner on their respective block, and had to endure the harassment of Republican prisoners.

These incredible stories only scratch the surface of what is the expanding study of combatant women in Northern Ireland and beyond. In my analysis, I found that historical precedent and ideological affinity for feminist attitudes were major influences in how these women experienced their respective paramilitaries. For example, all-women Republican paramilitary groups like the Cumann na mBan, founded in 1914, acted as a strong foundation for Republican women’s participation in the Troubles. Similarly, ideologies like socialism, which greatly influenced Republicanism, place a larger emphasis on gender equality than the traditionalism that influenced Loyalist ideology. Furthermore, understanding these differences is important not only for understanding the role of women in the conflict in Northern Ireland, but also for situating women as combatants in conflict worldwide. Often, women who engage in violent conflict are categorized as one-dimensional actors, particularly seen as victims rather than active participants. In order to gain a fuller and more complete understanding of conflict and those it affects, we must not overlook the experience of women, but rather work to understand their multifaceted experiences and identities. Shining a light on Republican and Loyalist paramilitary women is a necessary step in this process.

1 More information on Jackie and Sinéad can be found, respectively, in Miranda Alison’s Women

and Political Violence: Female Combatants in Ethno-National Conflict and A Kind of Sisterhood

directed by Michele Devlin and Claire Hackett.