Fire Sirens in Jan Carson’s The Fire Starters

Ainsley Atwood is a student in the School of Foreign Service studying Culture and Politics, with minors in English and French. She was a part of the 2023-24 cohort.

In Homer’s Odyssey, sirens take the form of either women or birds, known for their singing which lures sailors onto the rocks. However, in the epic, “the sirens do not perform as expected; they sing, but their words appear to describe a narrative song they would like to (and never do) sing for Odysseus” (Schur 1). Instead, the sirens only command Odysseus to listen to them, promising the reward of such a song (4).

Jan Carson’s 2019 novel The Fire Starters places these beings in the context of East Belfast, “sixteen years after the Troubles” (Carson 7). The action of the novel takes place in the weeks leading up to the Twelfth of July, a Unionist holiday commemorating King William’s victory at the Battle of the Boyne (Poloni 115). On the eve of the Twelfth, Unionist communities burn bonfires, often festooned with Republican symbols, such as Irish flags and effigies of Sinn Féin leaders (113). Many see these bonfires as “a legacy of the Troubles” (121), and within the novel, many make efforts to leave them in the past. Amidst concerns about the height of bonfires posing a safety risk, legislators implement restrictions on the heights of bonfires. However, these restrictions prompt arson attacks across East Belfast, protesting the new laws (Carson 18).

These arson attacks, known as the Tall Fires, are the backdrop to the story of Jonathan Murray, who is in a predicament nine months after a sexual encounter with a siren. Jonathan suspects that this siren has been manipulating the young men of East Belfast into starting these fires across the city. Jonathan finds himself with a baby daughter named Sophie, whom he fears may be capable of the same kind of manipulation that he suspects her mother has been doing. His actions with regards to his daughter are shaped by this fear, and as it becomes more and more difficult to avoid Sophie hearing and learning words, Jonathan decides to cut out her tongue to stop her from exercising any siren powers she may have (199).

Jonathan’s plan to cut out Sophie’s tongue is a literal representation of the way in which silence is intertwined with fear and acts of violence, especially in the years after the Troubles. He views the act as a necessary way to prevent the violence of the arson attacks, despite the fact that he knows Sophie has nothing to do with the fires. At one point, a patient of Jonathan’s notes that there’s only a fifty percent chance that Sophie has inherited this power from her mother (Carson 248). In planning to cut out her tongue, Jonathan intends to punish Sophie for the sins of her mother and of the arsonists, all for the sake of a fear that may be unfounded.

Sophie says her only syllable at the end of the novel, when Jonathan is preparing to cut out her tongue. This syllable is enough to make Jonathan “drop the needle” he was using to administer anesthetic and abandon his plan (Carson 289). Just as in the Odyssey, Sophie does not get the chance to communicate in a clear and nuanced way; instead, her speech acts as a command that Jonathan is powerless to disobey. Jonathan’s inability to act in the face of Sophie speaking is comparable to a parent’s reaction to their child babbling for the first time, conveying that the power of Sophie’s words is not unique to sirens like her—any child could grow up to use speech for better or for worse. Though Jonathan’s plan to cut out Sophie’s tongue is intended to stop the Troubles’ legacy from affecting the next generation, it only serves to perpetuate the violence that has continued in the years after the Troubles. Sirens are a paradox. When they speak, they are agents of destruction; however, they never speak how they say they will. Jonathan is in an equally paradoxical situation as he attempts to prevent an extension of the Troubles through violence of his own. The Fire Starters is not just about the dangerous potential of women speaking, but also the anxiety which surrounds women’s speech. This anxiety comes with its own dangers, especially when it appears to justify acts of cruelty to those who cannot defend themselves. These acts, however temptingly simple, do not achieve their promised ends, much like the sirens in the Odyssey.

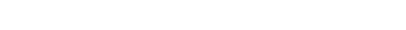

Miniature terracotta squat lekythos (oil flask) with siren, mid-5th century BCE. Photo credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254295

East Belfast bonfire, July 11, 2008. Photo credit: Alan in Belfast. https://www.flickr.com/photos/alaninbelfast/2660750702/in/photostream/

Sources

Carson, Jan. The Fire Starters. Doubleday Ireland, 2019.

Poloni, Anna. “Bonfire Time in Belfast: Temporalities of Waste in a Loyalist Neighbourhood.” Etnofoor, vol. 33, no. 2, 2021, pp. 112–32. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27090778. Accessed 30 Mar. 2024.

Schur, David. “The Silence of Homer’s Sirens.” Arethusa, vol. 47, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1–17. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26322591. Accessed 14 Oct. 2024.