Ireland and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Extraordinary Times Call for Ordinary Measures

Isabella Turilli graduated with a Bachelors degree in Science, Technology, and International Affairs, with a Certificate in Diplomatic Studies, from Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service in May of 2022. She was a Global Irish Studies Fellow during the 2021-2022 academic year.

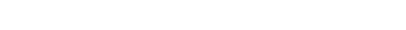

As it stands now, COVID-19 is actively changing our world. When it erupted into the global consciousness in early 2020, few had an accurate understanding of the new normal a pandemic would usher in. From the advent of universal masking to the downfall of international travel, we are still navigating this new normal.

Just as people struggled to adjust their daily lives around the virus, national governments scrambled to create legislation to address the crisis. In Europe, the majority of states declared a state of emergency or implemented a statutory regime aimed at creating a temporary legal environment specific to the conditions of the pandemic. A small minority of states – Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Ireland – decided against this path, choosing instead to pass ordinary legislation.

In Ireland, the use of emergency powers has historically been synonymous with violent political disputes. The Republic of Ireland frequently relied on extraordinary powers to fight against paramilitarism; Northern Ireland was primarily governed through emergency powers for most of its existence. The island is all too familiar with the perils of overreliance on states of emergency. It is unsurprising then that the Republic’s own constitution features a remarkable reticence towards the use of such powers. While many countries simply require an unqualified, if major, threat to their sovereignty to employ a state of emergency, the Irish constitution restricts its use severely. Article 28.3.3° permits emergency legislation only “in time of war or armed rebellion”–a legal quirk that informed the decision to address the pandemic through ordinary legislation.

This route was not without controversy–many saw the legislation as a crucial and irreversible contributor to democratic backsliding. Fears of human rights derogations ran rampant, with onlookers worried that restrictions on movement and public gatherings might become permanent. As autocratic-leaning leaders took advantage of the crisis to bolster their own power, there was concern that enshrining pandemic regulations into the regular legal canon would “result in executive decision making that is all but unaccountable.”

Though such fears are not unfounded, it is worth examining the recent history of emergencies. The name itself connotes rarity; by definition, an emergency is a situation that is unforeseen, sudden, and demanding immediate response. Yet the legal use of states of emergency, particularly in Western countries, is nothing if not common. Emergency powers have been a staple feature of democratic governance for the past century, having been applied to everything from economic regulation to war. In the words of the International Commission of Jurists in their 1983 Review, “It is probably no exaggeration to say that at any given time in recent history a considerable part of humanity has been living under a state of emergency.”

The dichotomy in the “normal-versus-emergency” paradigm is at best false, and at worst, useless. Used properly, a state of emergency should be self-destructive, with the regulations expiring alongside the emergent situation. A near-constant state of emergency denotes an inability for “ordinary” legislation to handle even the slightest shifts in the norm. In a legal environment that lacks a robust “normal,” every regulation will problematically hybridize itself, allowing the executive the breadth to use an “emergency” to gain control of any purported crisis. The accrual of power might be slow, but it will eventually build to an insuperable degree. Hence the problem changes: it is not the one-off, expiring state of emergency, but its repeated use against a varied spectrum of perceived threats, that may contribute to the consolidation of executive power.

All of this is complicated by the fact that the emergency at hand is unique. A global health emergency–or as the World Health Organization terms it, a public health emergency of international concern–is not a debt crisis or a war. Successfully addressing it requires not only the adoption of containment and quarantine regulation, but coordination of such measures on a global scale. A virus cares not for political boundaries: a well-managed outbreak in one state means little if its neighbor has let the disease run rampant. The timescale of the pandemic adds an additional dimension–COVID-19 has lasted for more than two years, and shows little sign of going away anytime soon. We are thus faced with the question: how do we build laws to address an emergency that requires an immediate and drastic response, but will last long enough to imperil the health of a democracy?

In this light, the Irish approach to the pandemic might make the most sense. The adoption of “ordinary” laws in the face of an emergency gives a country legal memory of the crisis response, eliminating the need for a revolving door of extraordinary legislation for each threat that comes around. This strategy also means these laws could be used for more than one kind of emergency–a legislative version of “reduce, reuse, recycle” that clarifies what citizens can expect during a period of crisis. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, this approach allows for a more realistic understanding of modern emergencies. Between the heightened likelihood of multinational disease outbreaks and the shadow cast on the future by climate change, governments must begin legislating for long-term crises without sacrificing either democratic values or the rights of citizens.

This is not to say the Irish response to COVID-19 was perfect. From the complaints about the poor parliamentary oversight over pandemic regulations, to Trinity College’s 101-page report on potential human rights violations, Ireland’s handling of the pandemic has faced its fair share of criticism. But the choice to view the pandemic not as an emergency, but as a “new normal,” may be a useful strategy in negotiating a world where threats reach wider and last longer than ever before.